Episode 73

DRM with Jeremy Keith and Doug Schepers

June 13, 2014

DRM has been long touted as the solution to piracy. Recently, a few browser makers and big media companies have pushed DRM technology into the web browser — while open web advocates have fought to prevent DRM on the web. What is DRM? Why and how are companies putting it into web browsers? And what solutions would be better? Jeremy Keith and Doug Schepers join Jen Simmons to debate DRM on the web.

Transcript

- Jen

-

This is The Web Ahead, a weekly conversation about changing technologies and the future of the web. I'm your host Jen Simmons and this is episode number 73. I first, of course, want to say thank you to the sponsors of today's show, Squarespace and the Velocity conference. I'll talk more about those later.

The topic today is going to be DRM, Digital Rights Management. Which is a big thing. It's a thing that's been hotly debated for quite awhile among all sorts of people who have to do with technology and digital files but especially recently having to do with this show, the web. DRM and the web. Should there be a way to use DRM on the web or not, what do we want? So I thought for this debate / discussion, I should have more than one guest on. So today I have two people, both friends of the show, both who've been on the show more than once before. Jeremy Keith and Doug Schepers. Hello folks.

- Doug

- Hello Jen.

- Jeremy

- Hey Jen.

- Jen

- I'm just going to say so people know who you are. You're both awesome, you've been been working on web standards and helping to form what the web is going to be in the future. Being on email — debating, at length, on email — in person, at conferences, talking to people, writing blog posts, saying, "This is what we think the web should be, this is what we don't think the web should be." Because the web itself has been shaped by those exact kinds of conversations on email, in person, in blog posts, that's how we ended up with the web that we have today. Both of you have been super influential and active in those kinds of conversations and I know that you both have a lot of knowledge and a opinions about this kind of sticky situation.

- Jeremy

- I know that Doug has a lot of knowledge. I only have opinions, rather than the knowledge, basically. [Doug laughs]

- Doug

- I would like at this point to make my disclaimers.

- Jen

- Go ahead, yes, before we can start, we need some disclaimers. Some armor.

- Doug

- My disclaimer is, contrary to what Jeremy says, I am not particularly knowledgeable about this. That is to say, this is not the stuff I do at W3C. This is not something I do for a living. And I am not speaking, at all, for W3C, in this. This is not a W3C opinion. This is my opinion as somebody who's had a pretty good seat in the game and been watching from the sidelines and these are my thoughts only.

- Jen

- Ok. [Laughs] I know you both know tons more than I do about this, so, that's why you're here. But, yes. This is a very hotly contested issue, so we're going to start with disclaimers. Let's start by just explaining, especially for people who maybe, they've heard DRM and they kinda-sorta remember what that is but maybe they kind of don't remember which thing that is. What is DRM? Where did it come from?

- Doug

- It's evil. It's pure evil.

- Jeremy

- Well, DRM itself is a phrase, it's initialism, that stands for "Digital Rights Management". Which is a euphemism in the same way that "friendly fire" or "collateral damage" is a euphemism. [Doug laughs] It doesn't really describe what it's about. Essentially, it's trying to enforce the mutually incompatible idea that you could run something on a computer, execute something, but not be able to copy something on a computer. For example, a video file, an audio file, that you would be able to execute it without being able to copy it.

- Jen

- Yeah. It showed up because, if you buy a book, it's a physical book, it's a stack of paper that's glued together or stapled together or stitched together and you can't just sort of wave a magic wand and instantaneously have a clone. But with a digital file, you can. You can just hit "copy" or "duplicate" or something, and bam, you've got another copy.

- Jen

- Right. This is why, when those advertisements appeared at the start for DVDs, they were rightly ridiculed. They would say thing like, "You wouldn't steal a car. You wouldn't steal a handbag." When, actually, if I left a perfect copy of the original car in place, maybe I would steal a car, because I wouldn't be hurting anybody. I'd just have a copy of the original car. Nobody would have lost anything from that. The verbs used around this usually are things like "stealing", "taking"; I was "taking" a video, "taking" an audio file, but actually it's about copying. There's a fundamental difference in that. It's nondestructive. Digital copying is nondestructive. When you copy something, you've left the original intact. It doesn't have any effect. Other than affecting the scarcity of the original file.

- Jen

- Right.

- Doug

- I think you hit the key word. It's the "scarcity", right? I mean, scarcity is a complex topic. If I have a physical copy of a book, I bought this book, I can have a copy, I can have that copy, and nobody else can have that particular copy. I can lend that copy out, I can give it to somebody, I can sell it. But there's one of that copy of that book. And if I can make many, many duplicates, that underlying question is, with this artificial scarcity of saying, "oh, there's this digital version and only you can use it, only one person can use it," you have an inherent, sort of metaphor going on. Which is, the scarcity that we're introducing into the marketplace of only one person can have this digital version at a time, even though copying and distributing actually does not affect that original file...

- Jeremy

- Yeah, there was actually an interesting post recently, just the other say I came across, about this idea of "rare recordings". How it used to be, you'd have this concept of, "this is a rare recording of The Beatles," and you'd have this rare recording of somebody flipping out in a studio. How that phrase just doesn't really have any meaning anymore, because a "rare recording", it's been seen millions of times on YouTube, it's been seen as many times as people want to see it. "Rare", "popular", it just expands to fit however many people want to see it. Once you get digital, the idea of "rarity" or "scarcity" is kind of artificially imposed.

- Doug

- Right. It's that sort of thing, the rarity of it, to some degree, is in the distribution model. Is there a market for this? Right? Can we distribute this efficiently? Like you say, it doesn't matter anymore. Another part of rarity is, if I made a copy of my version of that rare recording, it degrades a little bit. Then, the next person, it degrades a little bit. So the rarity is also by the means of reproduction. Like you say, the digital version, there is no degradation of the signal as it's distributed. But I think that the scarcity that we actually should be talking about, when we're talking about the scarcity of a resource, is not the medium with which the resource was delivered, but rather the scarcity of the resources that went into making it. And the artificial scarcity here, the artificial scarcity of the book or the digital book or the DVD or the digital version of it, the online version of it, is an attempt to reflect the scarcity of the time, the skills, the resources, et cetera, that went into making the original work itself so that those people could be compensated. They're trying to economically reflect the scarcity of the people's time and the effort.

- Jeremy

- Well, while at the same time, trying to get it out to as many people as possible. This is where this push-and-pull, right? They're trying to get it seen by as many people as possible, but they want to be, they want to control how it's seen. Because, like you say, they put time and effort into it. Sweat and blood went into making something. But it's not like they're trying to not distribute it. They're not trying to keep it scarce. They actually want it to be seen by many, many people, it's just they want to control how it's seen.

- Doug

- I think that's a key sticking point, right? It's controlling how it's seen. I personally, I want to compensate people who have made stuff that I love. I think we all do, right? And I want to pay for stuff. And I want to do it in a way that's convenient for me. [Laughs] And that includes being to, once I pay for something, I want to be able to see that thing on whatever device I have. I don't want somebody to be able to control the way in which I consume the thing that I've paid for. The where, on what device...

- Jeremy

- I think that right there is actually the key sticking point. A lot of people think the key sticking point about DRM is that it's about preventing people copying the content, right? Preventing people being able to share a copy. But it's actually much more about controlling how you can consume it. So the sticking point for you, as a user, who wants to pay, has paid for the content — the book, the film, the music — is that you now can't treat it the way you would have treated the DVD or the book or the CD. That you can't make copies, you can't deal with it as you would in the physical world.

- Doug

- It's sticky. Because some people simply wouldn't pay for something if there weren't some gatekeeping mechanism that stops them from getting it for free. I've been watching TV my whole life, and I know it's different, I've paid for watching those TV programs by watching commercials or whatever. Some other way of compensating them through means that are not necessarily me directly paying them. I don't think we've yet got a model, an economic model, that really reflects the inherent desire to have as much as we want all the time and to also compensate somebody for their time. I think this is a really tricky situation.

- Jeremy

- Yeah, I agree, and I think just trying to graft the model from the physical world, where you pay a set amount for a unit — that unit being a book, a film, music, whatever — and if you want to buy it, you pay a set amount. That doesn't translate very well to the digital world, precisely because of the lack of scarcity, that non-degradation of copying. I agree, I think we need to look into other ways. Whether that's micro payments, patronage, tip jars, advertising as you said, there's various other ways. They all have issues but I think the one that's least suited is to simply try to copy what worked in the analog world, because it's just a fundamental mismatch with the way things work in the digital world.

- Doug

- For me, there's a really strong sticking point. I don't know about the laws in the UK but if I were to shoplift two movies from a store, got caught, I would get a fine of tens or hundreds of dollars. I would maybe get community service. I would have a misdemeanor on my record. Whereas, with the laws in the US currently, if I were to decrypt one DVD, or not one DVD, one digital movie, right? I would be subject to, first off, federal laws, much more serious. Tens of thousands of dollars in fines. Possible prison time. If we're really talking about modeling the physical world, the physical scarcity to the digital one, the punishments are disproportionate, at least in the United States and other places I know, as well.

- Jeremy

- Completely, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act is just out of control. I don't know anybody who thinks its a good piece of a legislation. Even the people who've used it, you know, who've wielded it, have wielded it with regret because it's just such a blunt instrument to use.

- Doug

- Again, it's not proportionate to the real world equivalent of that thing. That's gotta be changed. For me, personally, as somebody who works for W3C, it's problematic, right? Am I contributing? Is my organization contributing to these laws? Or, not contributing to the laws themselves, but to helping make a situation in which these laws can be enforced unfairly upon people.

- Jeremy

- Frankly, if you're involved in any kind of software that has a copy function, that software could theoretically be used to copy something that shouldn't have been copied. You, as the software maker, could then be liable under the DMC. It's really disproportionate, really out of control.

- Jen

- So, DRM... my understanding of it is that, a digital file, it might be a book, an ebook, it might be a movie, it might be something, anything, right? A photo. Normally, you can duplicate it very easily because that's how computers works. And DRM is applied by creating some kind of encryption scheme onto that file. So, a CD for instance, when CDs first came out back in the — what was it, early 90s? Late 80s?

- Doug

- Late 80s.

- Jen

- We had cassette tapes, right? Music was on cassette tapes. And then, before that, it was on albums and continued to be on albums, and then CDs came out, right? It was very easy, once computers caught up to technology, to take that CD, put it into your computer, and copy the songs off of the CD and put them onto your computer. Then when DVDs came out, replacing VHS tapes and VCRs, the powers that be said, "Oh, we don't want to do that. That's too easy. People will just stick their DVDs in the computer and they'll just copy the files. Let's encrypt those files." So they came up with all of these complex encryption schemes so that it's sort of supposed to be harder to take a DVD and be able to get the movie off the DVD. Of course, we all know of ways, perhaps, some of us, perhaps some of the listeners know of ways that they might be able to...

- Jeremy

- That's the thing. All of those kinds of methods, they ended up hurting the people who had paid money. The people who had already bought the DVD were the people who then lost out when they wanted to make a copy for their own use, you know. Because they were switching devices and they still liked that movie.

- Jen

- Getting rid of their DVD player, maybe.

- Jeremy

- Yeah. For example, they think, "Well, I still own that movie, that's my movie." That's the way they think about it, although, actually, technically it's a license. But yeah. It would not prevent serious pirates. People who want to make multiple copies of movies to sell illegally. None of those schemes would have any affect on them. Because all of these things can't get around the "analog hole" as it's called. Where, you're trying to encrypt something, at the same time you want to allow it to be viewed. At some point, photons have to be emitted from a screen, and at some point air needs to be vibrated to make the noise and you can't control that. You can't control the light. Although, you know, 3D and movies seems to be doing a pretty good job.

- Jen

- The debate of, should there be DRM or should there not be DRM on these digital files, is in a way a debate about, should corporations, because usually these are big corporations making these decisions, should there be... or, us, too. I mean, this podcast, The Web Ahead, I guess, could have DRM on it. It does not. But the question becomes, do we want to encrypt our files in a way where we're trying to control whether or not people can copy it? We're trying to prevent people from copying it. I know someone who's a photographer who puts the photos up on the web so that people can see them but he doesn't want people to copy them. He wants people to pay him for copies and he'll send them a copy. So he's trying, he's using all sorts of different ways to put it onto the web page thinking that then people won't be able to get it. I was teasing him once, I was on the phone, and I just started grabbing a screenshot program, a just screenshotting it. It was making little camera sounds and I was like, "There I am! Not copying your image!" [Laughs]

- Jeremy

- It's interesting that you bring up photography, because a lot of the discussion around DRM to do with the W3C has been around this EME proposal that mostly around the video and audio elements and how to encrypt what's being delivered through them. But not the image element. Nobody is fighting the corner for photographers who want to protect their images. In fact, right from day one, you've been able to put images on the web and you've been able to copy the images on the web. But there isn't the same level of consortiums of photographers with enough money to lobby governments and lobby standards organizations and browser makers to get the rights of photographers respected in the same way that the rights of, say, film makers or musicians. It comes down to simply the money behind it. So it's interesting that the arguments for why it's wrong to copy video, music, it doesn't seem to get applied to images. Or, if it does, it's allowed to just simply rest on the moral argument that, "You shouldn't do that so please don't do that." Whereas with video and audio it's, "You shouldn't do that so we're going to try and prevent you from doing that. We're going to try to actively stop you from doing that."

- Doug

- And it's not just images that are not protected by this, it's also not text content.

- Jeremy

- Yup. There isn't a consortium of poets lobbying Congress.

- Doug

- Yeah. [Laughs]

- Jen

- Right. So, let me jump in here first with a sponsor and then we'll talk about... I'd like to just sort of outline for people the history a bit of DRM on the web and how that discussion has been going and where it started and all. But before I do that, let me tell you about the Velocity conference. O'Reilly Media has a conference called Velocity which is coming up in Santa Clara in June of 2014, this year. They also have several others, in Beijing, in New York, in Barcelona, in August, September, and November. So if you're listening to this later, feel free to go to velocityconf.com and see when the next one is, if you are, perhaps, interested. Velocity's a conference all about web operations and performance. It's for the people who are in charge of making sure web applications get updated and that the web is fast, scalable, resilient, and highly available. Things that we haven't talked a whole lot about on this show, as far as like, how should you best set up your servers so you can back things up automatically? And deploy new code on a daily basis without it being really complex? But there's a whole world of figuring out how to do those things, especially for large scale applications. This whole conference is all about that. They wanted me to tell you, we've got three things to tell you about that are kind of cool besides the conference itself. They have just put out a brand new report called, "Webpage Size, Speed and Performance" by Terence Dorsey and it's free. You can go to oreilly.com/velocity and download it. You can also go to the show notes for this show, which will be at 5b5.tv/webahead/73 and there will be a URL for all of these things, all of this stuff will be there. Go check out this report. Brand new, all about webpage size, speed and performance. They also wanted me to tell you that they're going to offer a special for the listeners for this show. An exhibit hall only pass to Velocity in Santa Clara, where instead of paying the $195 that you would pay just to go to the exhibit hall pass, you can pay $39. So if you're in California bay area and you want to drop by and see the conference and see what's going on, this pass, the exhibit hall pass, will get you access to going to speakers and author hours, and you can meet the speakers and authors who are at the conference there. A chance to network in the appointed career zone. A chance to attend the sponsored sessions track, where sponsors of the conference are going to be giving talks. Attend all of the extracurricular activities for Wednesday's and Thursday's events. Hang out in the hall for the famous Velocity hallway track, where you can meet people and go to lunch and just, you know, some of the best stuff in the conference is what happens in the hallway. They've got schwag that you get. You get a lot of different stuff for this $39. You can get the exhibit hall pass price by using the coupon code JENSENTEXPO or you can get 20% the whole event by using the code JENSENTME. There's also a conference, for those of you who can be in the area that week, there's a contest where they're giving away one free pass. You've got until Sunday, June 15th, which is three days from now, coming up really soon. A chance to win a two-day pass to Velocity Conference. Publish a web performance speed tip somewhere out there on the web, let me know about it by using the hashtag #fastwebahead or pinging me @thewebahead or on my website, jensimmons.com/contact. There's a whole bunch of more information about how to do this contest, what it is that you need to put out there, so just go to 5by5.tv/webahead/72 or /73, both episodes will have all the details about that contest. I think that's everything. Quite a lot of things. O'Reilly's a big supporter of the show and they really want you to know about this conference and all of the different things you can get from it. They also wanted me to tell you that none of O'Reilly's ebooks have DRM on them.

- Doug

- [Laughs]

- Jeremy

- Excellent.

- Jen

- You can buy ebooks from O'Reilly! This really goes right back into what we were talking about. When you buy the book, you can then just make bunches of copies, and you can put all of those copies on your different computers, on your backup, on your Time Machine, on your ePad, and on your iBook, and on your, whatever, this-that-and-the-other. ePad. iBook. iPad and... [Jen and Doug laugh] Whatever device you want! And you're not going to get annoyed by trying to open a file where it says, "I'm sorry, you need to put in your password" or you need to do this dumb thing. Or it doesn't work over here. Their argument is, and I think that this is proven out, they're a company, they make money. They believe in the kinds of values that we all share around the web and wanting things to be open, but they also, I think, I think, have found that putting DRM on the ebooks is not going to make them more profit. It's actually just going to drive their users crazy and make people not want to buy ebooks from them. Instead, they can be competitive, perhaps, with some of the... you know you can buy an ebook from O'Reilly and it's not going to have DRM or maybe if you buy something from somebody else it will. There's an argument to made, you could make more money.

- Jeremy

- Yeah, in fact, what you're doing is, you're saying to people, "Hey, it won't be a pain in the ass. Don't worry about it. There won't be any of this hoop-jumping that you have to go through when you're changing computers or you're switching devices." A Book Apart do the same thing. You pay the money, you get these files, you get the physical thing and we're not going to do DRM. We're going to trust you not to distribute it everywhere.

- Jen

- Right. Please don't be a jerk.

- Jeremy

- Yeah.

- Jen

- Yeah. And say with Hollywood movies, I think Hollywood is the most nervous and most backwards-thinking about this. You want to buy a movie, you want to buy it legitimately, you want to own it. You can go to Apple iTunes store, you can go to Amazon store, get the Amazon-whatever-they-call-it-place, but then we have to make a decision, right? I have to make a decision about which ecosystem I want to sign up with and I can't really transfer that file from one ecosystem to the other ecosystem. It sort of works on this set of devices or that set of devices, it doesn't really easily go back and forth.

- Jeremy

- Again, this comes down to the control. They want to be able to control how you consume it rather than it being a choice for the user. It's kind of the opposite to the way the web works. Think of the web as... it shouldn't matter what user agent you have, what browser you have, what network speed you have, what kind of operating system your computer's running, that when you access a URL, you get something. It won't be the same on every device but you get something. This back-and-forth, two-way conversation, it's sort of the way the web works and has done from the start. Whereas this is about the producer dictating that, "Ok, you can have this but you must use this particular device," or "You must use this particular software," right? So it's about dictating the terms of engagement. Which is essentially about what having the idea of having DRM in HTML is about. Is about dictating how content can be viewed. Which is a very un-webby approach.

- Jen

- So talk about how... I don't know which one of you wants to explain the history of what happened. Why are we talking about putting DRM into web standards?

- Jeremy

- Doug, I think you've been on the sidelines.

- Doug

-

Yeah. [Laughs] I want to say three things. I want to talk about three things. I want to talk about EME, specifically. I want to talk about iTunes. And I want to talk about WOFF or web fonts. Because all three of those are case studies here.

We're going to start with iTunes. iTunes had DRM when it first launched. You'd buy this music and you'd buy an mp3 and you could only use it on Apple devices. It had this DRM. Then people didn't really like that. People put up with it but they didn't really like it. Apple came out with this scheme where you could pay extra to pay for the DRM-free version. Then it was a choice. You could either pay the regular price or you could pay a little bit more so you could have freedom to do what you wanted with the mp3. Then they just went completely DRM-free. It's interesting. Would that same model happen with movies, right? Would it start off, would the web start off with the more restrictive way of accessing them, then over time through market pressure, would it be that people had less and less of a pain to buy a particular thing? Would content owners start not using DRM in order to spread their market even wider and to get even more possible revenue? And at what point would they do so? Would they, like, maybe have a DRM on the movie for the first year of its life and then give you the option to, you know, [laughs] pay for the DRM-free version? And then, later on, like five years later, it's DRM-free? But the question is, is that the world that we would end up with? I think that's questionable.

- Jen

- My understanding of what happened there is that Apple wanted... I mean, CDs didn't have DRM on them, right? That was already the status quo. The music industry really had no way for people to buy digital files. They weren't selling them anyplace. Then Apple came along and said, "Hey, we have this idea, we want to build this store, you're going to put all of your music on the store and we'll sell it for you and there will be no physical product." The music industry was like, "What?" A lot of artists were very hesitant, a lot of record labels were very hesitant, but a lot of them signed up. But I think the only way Apple was able to convince them to sign up is by adding DRM into the mix and making this promise about DRM.

- Doug

- Yes.

- Jen

- I think Apple from the very beginning, my understanding is, from the very beginning wanted to do DRM-free. But they couldn't get the record labels to agree so they negotiated and they did the DRM. Then later, like you said, yeah, I think it was 99 cents per song on average, usually, standard price. Then they said, "Ok, we'll do $1.29, you can do DRM-free version." I think finally in the end Apple got their way and they were able to say, "Look, we need to get rid of DRM completely on all files." Now if you have a bunch of old Apple files that have DRM on them, the store will actually replace them.

- Jeremy

- That's good because I know people who bought files back then who didn't realize they were DRM'd. They just thought, "I'm buying music." They were making that association with how they bought music in real life. They had no idea that when they needed to switch from using an iPod to using some other generic mp3 player or audio player, that they wouldn't be able to move those files. They were quite surprised.

- Jen

- I think it's gotten better and better in all of these subtle ways that we don't even quite notice. But I remember, back in the day, my computer would die. The hard drive would die or something. I would buy a new computer and then copy all of my stuff over from my old compute or my backup into my new computer and then I'd try to open up all of these music files and they wouldn't play.

- Doug

- Right.

- Jen

- It would just be like, "No. You're not the owner of this file." It'd be like, I am the owner of this file, I just have a different computer right now. [Doug laughs] That slowly has disappeared to where... sometimes I still stumble across that error of like, no song for you.

- Jeremy

- Yeah. It was a bad time.

- Jen

- But I think what happened, too, this happened in a lot of ways. Where Hollywood and the video industry came to this later, right? Music was easier. It was easier for computers to handle music files in the history of computers becoming powerful than to handle video files, and especially feature-length films that are high-resolution. I think Hollywood looked at what the music industry went through and said, "We're not going to let that happen to us." I think as Apple has come through and they're now famously trying to get deals for Apple TV, to get these big distribution deals to put out other software, I think they keep hitting walls in Hollywood where Apple's just not able to convince these guys. These guys are like, "No. We saw the music industry..." quote unquote, "... get screwed over, we're not going to let that happen to us." I think they're being much more stubborn.

- Doug

- I'd like to talk about another industry. Web fonts, right? The font foundries. Just briefly. The capability to have nice fonts on your website is something that designers have wanted since we had the ability to put fonts on the web. The problem there was that the industry was not, I say the producing industry, was not willing to let their stuff get on the web. They were afraid of these exact same problems. They were afraid that once their font got out there, people would just copy it and they would reproduce it, they would spread it around. They would see their revenue stream just dry up. Microsoft came out with a spec, or not spec, I'm sorry, a technology called "EOT." Embedded OpenType. That let you put fonts on your computer — this only ever worked in Internet Explorer — it let you put fonts on your server and people could download them on the fly. But they were encrypted, right? It was DRM on fonts. We really wanted to bring this functionality to other parts of the web but Mozilla was just not having the DRM. Ultimately, it came down to negotiation and discussion and the font foundries were interested because they wanted to be able to expand their market to the web but they were also really afraid of what would happen. What ended up being the solution was something called "WOFF," Web Open Font Format. What people commonly call web fonts. What it is, is, when you make a font, it has a little license file that goes along with it that says, "Hey, the name of the font is this, it comes from this place," you know, this font foundry, "This person licensed it and they licensed it to use on these websites." That is enough information for the font foundries to be able to say, "Hey, you, person over here, you're using this font illegally." That's enough of a legal mechanism for them to say, "Hey, you are not licensed to do this. Stop doing this." To sue someone for misusing one of their fonts. I think that's a model we should look at really carefully. Because that ended up being enough of a... it's not a particularly deep technological solution. It's a very lightweight technological solution. It expresses where somebody is allowed to use that font. I think that's a really interesting model that might be something we should look at for other kinds of media.

- Jeremy

- I agree. I remember this coming up at the browser wars panel at SXSW a few years ago. Chris Wilson was still working on IE. And IE would only parse the EOT files, which, as you say, which were DRM'd. Whereas, Mozilla would not have anything to do with DRM. It was this kind of deadlock. You can have fonts but only on Internet Explorer. That's no good, right? That's not very webby. But to me the solution wasn't actually WOFF. WOFF was almost like this face-saving solution. Because it allowed the foundries to be able to say, "We feel like we're being placated here. We've got this way of embedding our licensing information that isn't DRM." And it allowed Mozilla to go, "Ok, well, this isn't DRM so we're okay with supporting OWFF, that's fine." But actually what allowed us to use web fonts on the web all the time was third parties. It was people like Typekit and Fontdeck figuring out, "How can we please the type foundries and please the users and get something workable for both?" I think that's how it worked out. I think that's something that's worth looking at, as well. Right now the studios are looking at, how can they control everything? Maybe, as you said, iTunes came along and Apple figured out the way to do it. Not the music industry. Apple Computers figured out the way to digitally sell music. With the fonts, I don't think it was WOFF. I think it was Typekit and people like that figuring out how to act as a negotiator. But I agree, it seemed like WOFF was just lightweight enough that it placated that font foundries. That they felt like their needs were being heard. But it wasn't DRM and therefore anti-DRM groups, open source groups, could implement it.

- Doug

- I actually think it was a combination. I think that we wouldn't have been able to have things like Typekit and other things if we had not done WOFF as well. My impression, talking to the font foundries, is definitely that WOFF was the thing that made them feel comfortable. Having the expression of what... I agree with you, absolutely. That it took particular people to do the market. But I think that having the standard there was what made those things possible.

- Jeremy

- Yeah, but it's interesting because the type foundries kept saying that they wanted a way to stop people copying their fonts. That's not what they got.

- Doug

- Yeah, no, it's not what they got.

- Jeremy

- They got a way to label their fonts.

- Doug

- Yup.

- Jeremy

- Like I said, I think WOFF was super important. Really, really valuable. But I think it was almost this face-saving mechanism. It allowed everybody at the table to say, "Yes, we feel like our needs are being met." Even though it's not DRM and it's not going to stop anybody copying a file. Yeah, it allowed everyone to feel like they were being heard.

- Jen

- It's interesting, too, that the solution that we ended up with doesn't stop piracy but it also opened up, [laughs] the kind of market that the type foundries have probably never imagined in their wildest dreams. I mean, the way everything has been... it's fonts now. Everything is just, find gorgeous typography. Start there. That's your graphic design. That's for the web. That's for your product. That's for your app. That's for your packaging. Of course fonts have always been a big part of graphic design, and very important since things went digital, especially since things went digital in the 80s. But it's just, I don't know what the numbers are. Take what was going on before and put some zeros at the end because the market's just so much bigger for type foundries now.

- Jeremy

- I remember at this panel when Chris was saying, "No, we have to have DRM in the fonts because fonts are different." I was saying, "What about photographers?" You just allow images to be viewed in a web browser with no protection, no licensing whatsoever. And trying to make that argument that somehow images were different. Doug, as you said, text. Somebody puts a poem or screenplay on the web. That's protected but browsers aren't going out of their way to add any kind of protection for the people who produce those kinds of works. It is weird how it's fairly selective which kinds of things get the protection. Which kind of things get the movements behind them.

- Doug

- I'll say this, one thing that worries me, about text for example. When EME started to get some traction, some people said, "How can we apply this," publisher's, for example, "How can we apply this to our content? Sure, it's great that you have that for video, how can we apply this to our books? How can we apply this to our journals?" Et cetera. It's that slippery slope that I'm concerned with, right? The battleground here is for more than just media. It's also for all content on the web. You mentioned earlier, Jeremy, the idea of web payments or micro payments, these things. W3C has started work on those things. I think those are going to be a big part of the solution. I think we need to get this right because of the implications of what this could mean for the web in general. How open the web can remain.

- Jeremy

- Yeah.

- Doug

- When we think of payments, for example. I would, personally, much rather pay somebody on their blog [laughs] a nickel or a penny or whatever it is, for my visit. Rather than have to have all those ads loaded and blinking in my face. I would much rather just have an account that pays out a penny or a nickel or whatever every time I visit that blog. Or have the option of looking at an ad instead if I don't want to pay it out. I think that would be a more direct and more honest compensation for somebody's effort than to have to have this middleman of advertising. Which, frankly, I don't pay attention to.

- Jeremy

- I agree, I think it would be more honest. I think it's more honest to the medium. It's more honest to the fact that this is digital and you get the network effects of a large amount of people paying a small amount of money, it's going to add up to a large amount of money. Rather than trying to borrow the model from the analog world where one person pays the same price. I agree. But looking at EME, it doesn't look like what EME does it provide a solution. It seems like EME is providing a framework for people, publishers, to build their own plugin systems. It seems like a way to build plugins within the browser. Is that a fair representation of EME?

- Doug

- Yeah. I think it's a fair representation. It's not exactly accurate from my understanding of it. EME is not DRM per say. It's only used as DRM but it is not a full DRM solution. EME provides hooks, an API, into the browser. Between the browser and the underlying platform-level DRM solution. Or it doesn't have to be platform level. The plugin isn't actually in the browser. It's the system that is underlying on either your device or in your operating system or maybe it's a third party piece of software that you installed. Mozilla, in their implementation of EME, is making this really explicit. The others aren't making it as explicit. They're just making it a more seamless sort of experience for the users. Mozilla because of their obvious quandary with doing EME at all, or DRM at all, is making it so that it's an... at least now, they're making it as an opt-in thing. You actually have to take a step in other to enable it. I understand where they're coming from.

- Jen

- So back up a moment and tell us what happened. The web started out with HTML, CSS, content inside the HTML, images. Everything was open. Nothing was encrypted. And then somewhere along the way, somebody started saying, "We need to have DRM. We need to be able to encrypt audio and video," I presume, as you said before, Doug. Where did this tension start to affect...?

- Jeremy

- As I understand it, this fear that the web was going to lose out. Because very large players like Netflix, for example, were saying, "Look, if the web can't provide a way for us to play back this content in a protected way then we're not going to use the web. We're going to use closed systems." Consoles, machines that do allow them to do DRM, that won't allow copying of those files. That's why I think, at the W3C and other places, there was this feeling, and browser makers, "Well, we have to play ball. Nobody wants DRM but if we don't provide these players with DRM then they're going to take their content and not provide it on the web." Now, from my point of view, my reaction is, fine. Take your content. Don't provide it on the web. We'll survive. I'm ok with that. That's not a very popular view and I know most people don't agree with that. But I'm actually ok with the fact that in my living room, I've got this Apple TV which is a completely closed system, right? I can't install anything on it. It doesn't even run a web browser even though it's connected to the internet. It's a very closed system. And I subscribe to Netflix and it provides DRM'd content to me on my closed Apple TV system connected to my television. I'm ok with that. Now, some people would say that I'm being a complete hypocrite to say, "Well, why shouldn't we have DRM in the browser and on the web?" My answer is that, it's the web. It's got a different viewpoint, frankly. A different spirit to it. Which is, share what you know. Like you said, the web came about and you put files up there, files can be moved around, that's the way the web works. To take the closed system approach and apply it to the web fundamentally changed the nature of the web. And I'm actually ok if Netflix and these other media producers say, "Fine. We're not going to use the web as a distribution mechanism. We're going to use closed systems. We're going to demand that you must have a particular piece of software that you have to install. A native piece of software." I'm ok with that. I don't think everything needs to be in the browser. Especially if, by providing that functionality in the browser, you break what a browser is.

- Doug

- I can respect that. I have a very similar situation. I've got a Roku. I stream my content from Netflix, from Hulu Plus, from Amazon Prime. That's a very similar [laughs] closed ecosystem that I've got. And I can respect your decision and your viewpoint but I will say that the browser vendors don't share that viewpoint. And I don't think they will. The browser vendors, regardless of what W3C does, are going to put some sort of way to have these videos... you can already do videos, right? Technologically, you can already do audio and video in the web and that's not a problem. The question is, will the people who have the content, who own the content, let that happen? Let their content be used? That's the only question. That's a determination that the browser vendors, most of whom have... the browser's only part of their business. All of these browser vendors, and a lot of consumers, say, "Yeah, I want to be able to have this on the web."

- Jeremy

- This is where the W3C comes into it. Because, I agree, if the browsers are being strong-armed by these large media producers by saying, "We want to be able to provide our content inside your software. Give us a way to do that." I can understand that browsers are going to give them some kind of plugin architecture that will allow them some kind of DRM, even though it won't work. They'll conceded that. But I don't get that it needs to be blessed by the W3C. Because if browsers do start providing DRM then, worst case scenario, we can go build a new browser, right? We can build a new rendering engine? I don't want to do that because it sounds like a lot of work. [Doug laughs] But theoretically, you know, anyone can build a browser. That's kind of the whole point of these standards existing. Is that somebody can go, just given the standards alone, and could build a web browser. But if the standards themselves contain the instructions for how to build a DRM and that you don't have a standards-compliant browser unless you are implementing EME, then something has fundamentally changed in the world of standards. In the world of the web.

- Doug

- I actually... I see where you're coming from. I think that you're misstating a few things and I'd like to correct that perception.

- Jeremy

- Ok.

- Doug

- First off, I want to say, what I think the motivation within W3C to accept content protection was. I want to say, content protection is what was put into scope for HTML. Not EME specifically. I think that there are other solutions, things that are lighter weight. Things like WOFF that are possible alternatives but nobody has really come up with an alternative at all yet. Nobody has tried to come up with something that says, "This is not EME. This is a better solution." It preserves more rights, et cetera. More consumer rights. I would like to see something emerge. I think that W3C's motivation was, we are going to have this anyway. We're going to have this in browsers anyway. Let's make sure that it is as equitable as possible. That it works for accessibility. That the people who have accessibility needs are not locked out. That it's secure. That it is internationalized. That it has all of the other things that the web has. That the web standards have. That it is, as much as possible, royalty-free. I don't think that EME actually goes far enough. Because EME only describes the API that hooks into underlying DRM, I don't think that it actually provides enough of a royalty-free promise. I don't think that it gets rid of the platform lock-in that true interoperability would supply. I'd like to see a proposal that actually addresses those things.

- Jeremy

- I agree. I think a good way of looking at EME would be it's almost like a straw man. Ok, this is what people want. Here's a proposal. It's a terrible proposal. [Doug laughs] But you don't like it, give us an alternative, right? Come up with something better. Give us something more like the WOFF solution. The danger is, it looks like we're going to get stuck with EME even though it's terrible and won't work. And it was the first solution proposed. It looks like that's what's going through.

- Doug

- Well, I mean, it's got a lot of momentum. I think that the faster people act to actually come up with a good technological solution that is an alternative, the better the chance that we don't have to use EME.

- Jeremy

- Except, of course, it comes back to these studios again, these big players. If you provide an alternative that's clearly better, that's clearly more equitable, but Netflix and Paramount and whoever say, "No, we prefer that EME thing. That sounded more like what we want." Then it doesn't matter how good your proposal is. It doesn't matter how much more well-thought-out it is. At the end of the day, it sounds like the studios are going to get whatever they want.

- Doug

- I'm not sure that battle is over yet. I'm sympathetic to what you're saying but I don't think that battle is yet decided. EME is not yet a W3C recommendation. It is not yet blessed by the W3C. I think that content protection can be expressed in a number of different ways and I think that we should keep exploring those. I have some ideas, other people have ideas, but really, it does ultimately need buy-in from lots of parties. But W3C works on consensus. If we have people... like EFF joined W3C specifically for this issue. If we have enough people — "enough people", I say, entities, people, companies, et cetera — saying, "This is the solution we should use, not this other solution." I want to also say, though, that you made a statement that you couldn't build a standards-compliant browser without EME if EME became a recommendation. That's not true. I just want to be clear, you could have... nothing that W3C does is ever mandatory. It is all opt-in. We do not enforce compliance to our standards. EME is a sort of modular piece of HTML on the side. You could have a completely conforming web browser that doesn't do EME and that would be just fine by W3C or by W3C specifications. It's not an inherent part of the platform. It is a possible part of the platform. It is a part of the platform that everybody right now is looking at deploying, unfortunately in my opinion.

- Jeremy

- Yeah, I agree. Because, if nothing else, leaving aside the moral question of compensating people for works, blah blah blah, just from a technical point of view, it seems to be some fairly dodgy thinking. In my opinion, right? I don't know much about these things. In the way that EME works. In that it's providing a black box. In the same way that a plugin was always a black box to the browser, right? It's this thing that the user has installed and we have no idea what goes on in the plugin. That's none of our business. This is providing a way for content providers, as you say, to access lower-level APIs without the browser really knowing what exactly is going on. Which seems like a massive security hole if there are bad actors. Looking at the way that these studios have behaved in the past, like Sony providing root kits on CDs. The worst of cracker behavior. These are people who have proven themselves untrustworthy and we're about to provide them with the keys to the system, quite literally. There's a really great post by Henry Sivonen on how EME works. It's very dispassionate, disinterested, it's purely just from a technical perspective. It doesn't make a judgment call one way or the other. I was reading through it to try to get my head around how EME works. There are some phrases in there that give me the heebie-jeebies, right? At one point, it says, "events fired to JavaScript include byte buffers that contain messages in a format specific to the key system that's in use for this session. Neither the browser nor the JavaScript program understand the bytes." That right there. That terrifies me. That should scare me. I brought this up at the last TAG meet up in London. Alex Russell was saying, "Oh yeah, but your phone does that already." Again, this kind of goes back to my point of, I've already got my Apple TV running DRM. I've got these other closed systems running DRM. Just because an existing closed system works that way and has that anti-pattern, I don't want to see that copied over to the browser. I think we're both in agreement that EME is not the best solution for a number of reasons. Be it security, be it simply the fact that it just doesn't work that well and doesn't actually provide a solution. It just provides this kind of meta-framework for making multiple solutions. Yeah, I think we're in agreement that EME should not make it to last call.

- Doug

- Well, that's my personal opinion. [Laughs]

- Jeremy

- Yeah, likewise.

- Doug

- For a number of reasons. But I actually think that... I don't know if we're in agreement that a better solution might be for us to have an open web standard, royalty-free DRM or content protection scheme. I find myself in the unusual position of saying that I would rather that W3C actually did it's own DRM that is interoperable across systems, that is royalty-free, that is truly open, that anybody can implement, rather than do the half-measure of sort of enshrining existing DRM solutions that are less secure, less conscious of user rights, have more vendor lock-in, are not royalty-free or are license-based. I would rather that we do the full thing rather than prop up existing DRM solutions.

- Jeremy

- I agree. I think that would be the least worst solution of all of them.

- Doug

- Yes.

- Jeremy

- I do think there are inherent problems with having an open DRM standard because there is just such a conflict of ideas. There seems to be some cognitive dissonance, I think, with providing an open standard on how to DRM something. By it's nature the standard is available, therefore the encryption-decryption rules are available. But I agree, an open standard that we then give to these studios and say, "If you want your content to be on the web, here's the standard that you guys should implement." I would prefer that than the studios strong-arming the W3C to say, "Allow us to build our own case-by-case plugin." Which is kind of what EME is allowing. That Netflix can create their plugin, that Amazon can create their plugin, and Hulu can create their plugin. I agree, it would be better if there were just one solution. But I think there are inherent technical difficulties with trying to create a solution that stops people copying files. It's not impossible but I think it's very tricky and part of stopping people copying files has to, in some part, depend in some sort of secrecy, some sort of secret in the mechanism. And having an open standard for that means that the secret has to be open. It's a catch 22. It's tricky.

- Doug

- I don't agree. I lock my front door. Somebody could get into my house by breaking a window, by picking that lock, by doing other things, but it's enough of an impediment that the casual user doesn't walk into my house and walk out with my TV. It's still illegal for somebody to walk into my house and take my TV. Unless I ask them to. [Laughs] It would still be illegal to use this open standard to get access to and distribute content that they did not have the legal right to do. As you noted earlier, DRM doesn't work in most cases. For every DRM solution out there, there is already a crack, right? If you really want to get to something, if you want to bother to decrypt something, if you have more time than you have money and you want to find some way to get that movie for free and you're willing to invest, I don't know, two hours of your work so that you can save the $5 it cost you to actually buy a copy. Ok. Go out, get that solution, decrypt it, break the law, put yourself at risk, so you can save $5. Ok. If you want to do that, go ahead, right? But I don't think that there's an inherent difficulty. The thing is, the encryption mechanism would simply be there to prevent people from casually doing the thing that they shouldn't be doing.

- Jeremy

- I think this is where it comes back to what you mentioned earlier. That what's in scope is content protection, was that technically the scope for W3C?

- Doug

- Yeah, the scope is content protection.

- Jeremy

- Content protection. What you're talking about would provide content protection in the same way that WOFF does. But it wouldn't go as far as the current DRM solutions that we have which don't work anyway. So I agree that having an open standard for content protection is viable and would be very welcome in the same way that WOFF has turned out to be really, really good for web fonts.

- Doug

- I want to point out another thing about culture. That is, it is perfectly legal for me to take a portion of a video and include it in some other work. Maybe I'm making a review of something. Maybe I'm making some sort of mashup.

- Jeremy

- That depends on which country you're in. That would be Fair Use in the United States of America.

- Doug

- Right.

- Jeremy

- We don't have Fair Use in the UK. We have Fair Dealing, which is slightly different but it's more restricted here.

- Doug

- That's fair. I conceded the point. But I'm just saying that in the same country where it's illegal to decrypt something, but it is legal to distribute a reasonably small portion of a work as part of another derivative work. It's called Fair Use, as you said. Currently, DRM would not allow that expression of culture. That's problematic, right?

- Jeremy

- As it is currently, things like Amazon's digital products. Like Kindle books are technically violating the law in that they violate the law of first sale. When you buy a book, and this really goes back a long way, once you're done with that book you have the right to sell it. That right is the right of first sale. In the digital world, you don't have that right. I'm sure when we ticked the check box at the end of our end user license agreement there was something in there about that. But you're right, what these things do is they actually restrict the perfectly valid, perfectly legal uses of content.

- Doug

- So I don't want to get into... because I think it's a real rat's nest. I don't want to get any more into the physical versus digital bit. Because right of first sale applies to physical goods and things like that. But I do think that we should establish what sorts of rights that somebody has to digital things. I think that should be expressed in some combination of legal code and software code and standards descriptions. I don't think that there's an inherent contradiction between having open standards for open content protection and meeting the large majority of the needs from the content owners, the content distributors.

- Jeremy

- Except the problem is that those codes, those legal codes historically have been written by the people with the power, and that is the studios. That's not about the users, the end consumers. Now we're seeing that same power being exerted in the software world so that the code that's going to be written is going to be the code that pleases the content producers. Or the rights holders I should say because they're rarely the same people. Rather than the people who would be consuming this content.

- Doug

- I share your concerns. As a socio-economic status thing, this thing is out of control, in my opinion. It's a problem we deal with. I'll say this. You said that they've written low-laws, to some degree. I want to point out a difference between W3C and governments. One, W3C doesn't have enforcement power unlike governments. And two, we are not a pay-to-play. We work on a consensus basis. Consensus does not mean unanimity. It means, "Can you live with it?" If the majority of people can live with a solution, then that's how we arrive at our solutions. A lot of people were upset when the NPAA joined W3C as if that would affect how we make our decisions. It wouldn't. It doesn't affect how W3C makes its decisions. That's one more voice who can express their opinion. But ultimately it comes down to the technical, and to some degree social merits of the idea, as to what will be accepted. I still think that there is time. I still think that there is the ability for us to put forward something as an alternative to EME. I actually, even if EME makes it to our recommendation status, which is to say, our final standard status, and even if it is deployed, I still don't think that the battle is over. I still think that if we come up with a superior solution that more closely matches the social and economic requirements that we have, as well as the technological requirements that we have, I think that we can still win the future for a more open web. If we come up with a way to do so and if we apply public pressure to do so.

- Jeremy

- No, I totally take your point. I think that anger at the W3C is completely misdirected because this isn't like, W3C doesn't come up with this stuff and hand it down from on high and the browsers must implement what the W3C mandates. That's just not the way that standards work. Now if I'm going to be angry at anyone about EME it would be the browsers. The browsers that are considering implementing it. This is an unpleasant truth that the W3C doesn't like to hear but that the WHATWG acknowledge is that web standards or whatever is running in a web browser. It's not that the standards come first and then the browsers implement it, it's more of a two-way dance than that.

- Doug

- I agree with that completely. That's how we think about it at the W3C.

- Jeremy

- So actually EME getting implemented isn't something to blame the W3C for at all. It's something to blame the browsers for.

- Doug

- Yeah, sorry, I interrupted you. I just wanted to say, we totally acknowledge that it's implementation. In fact, actually it's sort of enshrined in W3C. Not to get too wonky on it, but the way that W3C works is that you can come up with a spec and that's fine but until you have implementations that show that that specification has market uptake, we're not going to standardize it.

- Jeremy

- Right, exactly. So it doesn't matter what the W3C comes up with. With Netflix, all of these other people putting pressure on them. What matters is what gets implemented in web browsers. If that's what matters, then those are the people that we should be taking issue with. Not the W3C. But the web browsers. Google, Apple, the people making the web browsers.

- Doug

- I don't want to pass the buck. I think that people should continue to press W3C for coming up wit ha good solution. I just think that they should be a little more articulate than the "because freedom" arguments that we've been hearing. I think that they should come up with real technological solutions and come to W3C and say, "Look, here is an alternative proposal that is also viable, that also meets these use cases and requirements."

- Jeremy

- Sure, as long as it's not begging the question. In other words, what you're saying is an argument other than "because freedom," provide another way to give us DRM on the web. What I'm saying is that DRM on the web in itself is not necessarily something that we need to do. We don't need an alternative solution to EME in order to provide DRM on the web in a different way. Question the fact that we need DRM on the web at all. Now, content protection, as you say, that's a different separate issue and that's what in scope for the HTML Working Group and that we could just about work with.

- Doug

- Right. And that's what I'm saying is, we should... I urge people to still keep thinking creatively about this and try to come up with some way that we can meet those use cases and requirements for the content protection.

- Jen

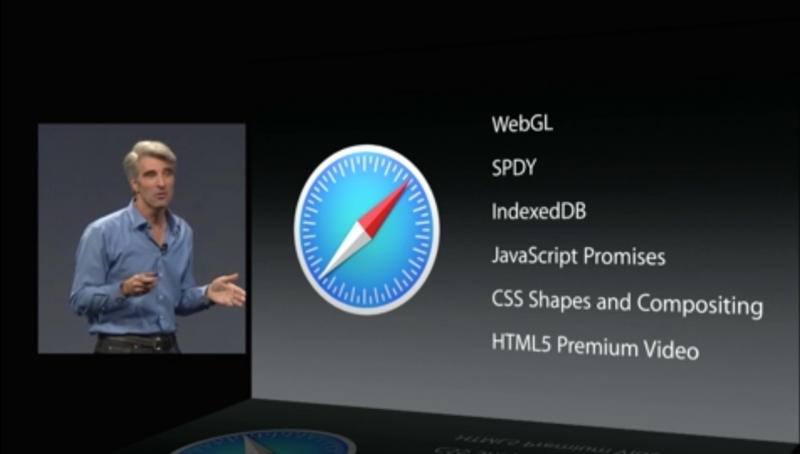

- It feels like a big weird circle to me. One thing that's different, especially with Hollywood films and these big distribution companies — like Netflix and whatever, whoever, all of them, Hulu — versus music, is Flash. Like, we've had Flash for how many ever years. A long time ago, it was the easiest way to get video on the web and it was the most user-friendly. If you wanted people to watch your videos, just put them in Flash. And HTML5 video gave us a chance to dump Flash, dump all the other extensions or plugins, dump Silverlight, and instead use just pure HTML elements for videos but that has no content protection whatsoever. And so these big companies don't want to switch. You guys know this but I'm just filling in for any of the listeners who may be a little lost. When Apple stood up at WWDC last week, they just really quickly put up one slide about changes in Safari and it just had six things on it. One of them, the last thing, was HTML5 premium video. Which is just sort of like, "Uh, what's that? That sounds great but what is it?" [Doug laughs] HTML premium video. And then Netflix put out a press release soon after. Here, I'll just read a little bit. "We're excited to announce that Netflix streaming in HTML5 video is now available in Safari OSX Yosemite. We've been working closely with Apple to implement the premium video extensions in Safari which allow playback of premium video content in the browser without the use of plugins." So basically you could drop Silverlight. And Silverlight is a pain. It's slow and it's just horrible. I don't want Silverlight. I want nothing. "With OSX Yosemite beta on a modern Mac, you can visit Netflix today in Safari and watch your favorite movies and TV shows using HTML5 video without the need to install any plugins. We're especially excited that Apple implemented the media source extensions, MSE, using their highly-optimized video pipeline on OSX. This lets you watch Netflix in buttery-smooth 1080p without hogging your CPU or draining your battery. In fact, this allows you to get two hours longer battery life on a MacBook Air streaming in Netflix in 1080p. That's enough time for one more movie." Apple also invented EME.

- Jeremy

- It's plugin by any other name. It's basically a plugin that's baked into a computer. Is essentially what they provide with that, and that's exactly what EME will provide, is a way for you to make multiple plugins. Like you were saying, Silverlight was a pain and Flash was a pain, we'll have a lot more pain because it's going be one plugin from Netflix and now Apple will need do another deal with Hulu and they'll do another deal with these other providers.

- Jen

- And then they'll ship them in the computer. In the operating system.

- Jeremy

- If you're making a film and you don't want to play ball with Netflix, you want to go your own way, well, tough. Getting that content viewed on the Mac and over the web because this is exactly what DRM provides. It's not about stopping people copying, it's about controlling how the content is viewed from start to finish and so you end up with these big players like Netflix who are going to have complete control from start to finish. That's just not good for the content producers.

- Jen

- Yeah, well, if they have some kind of competitive advantage because they can go and call up Tim Cook on the phone and go fly out there and have a meeting and get Apple to bake Netflix-only software into the Apple operating system, then you can't compete with Netflix in the future.

- Jeremy

- It's kind of the opposite of web standards.

- Jen

- Yeah.

- Doug

- I actually... Jen, you mentioned explicitly MSE. I want to differentiate MSE from EME. MSE is a way to let JavaScript generate media streams for playback. So it allows things like adaptive streaming and time-shifting live streams and things like that. MSE is not related to EME. They're being developed by the same groups but MSE is actually a really cool technology that will help the user experience. When they said MSE, that's actually a great thing. MSE is a great thing. EME is something separate.

- Jen

- Yeah, they mentioned in this press release. "MSE, EME and web cartography API."

- Doug

- Yeah, the web crypto API, ironically, is one of the things that I think is going to allow us a better, more secure web in general. The web crypto API is not specific to media. Web crypto API can be used for any kind of transactions. It could be used for WebRTC. It could be used for passwords, or, not passwords, it could be used for web identity, if we finally ever have a good solution for web identity. It can be used for all sorts of things that, for example, maybe hide your communications from the NSA. The web crypto API is actually quite good as well and that's also not related to EME> But of course like any cryptography or anything like that it can be used for the purpose of content protection or DRM or whatever. Like any other encryption thing can.

- Jen

- In some ways, this is a very positive spin and I think users will be happy to get rid of Silverlight. To get rid of Flash and to use HTML5 video instead is great. Two hours longer battery life is a great thing. So in a way lots of people are going to say, "What? I don't see what's wrong with this. This is a good thing." I think the problem, the frustration for many of us is we don't want to have to basically replace a plugin that the user's downloaded with plugins that the browser makers got. [Doug laughs] That the media companies got the browser makers to distribute secretly for them under the hood. We'd rather just have none. But, see, if there's no plugin, if it's just HTML5 video, you just use the video tag, and just right-click and save movie, that's why people don't want to use it.

- Doug

- Well, there's nothing wrong with right-clicking and saving the movie. Right?

- Jen

- Corporations.

- Doug

- Go ahead.

- Jen

- I mean, I'm not disagreeing with you guys. I agree with you. I'm just, it's just, like... Netflix is not going to let you right-click and save the movie. Or maybe Netflix doesn't care but Netflix is trying to do a deal with some big movie studio and the movie studio's not going to do a deal with Netflix if they know that their movies are then going to be one right-click away from being saved in a web browser. Right or wrong.

- Doug

- There shouldn't be any problem with me right-clicking to save the movie if I've paid for that movie and I want to watch it on the plane instead of live-streaming it.

- Jeremy

- Or it's a movie that your friend filmed of people you know and it's not a commercial movie. That's something else to remember, right? Movies don't just come from studios. That same way we talked about photographs and where's the photography protection? Well, photographs don't just come from professional photographers. This idea of a world where the content is produced by these big content holders like Netflix and is consumed by the rest of us... yeah, 99% of the case. But also, you know, we can make movies and we should be able to pass movies around and play movies just in HTML without DRM if we don't want to provide that DRM.

- Doug

- And just to be clear, nothing about EME would stop you from distributing movies without DRM if you so chose. It's not an inherent part of the video tag.

- Jen

- Right. You don't have to use it. You could still just use HTML5 video.

- Doug

- Yeah.

- Jen

- Underlying all of this, is this reality where the web was a platform most people didn't know about... not a platform, a space. It's a place that most people didn't know about where lots of people created work, put it out there, published it for each other, shared, wrote back and forth, had conversations, without any sort of... really just for the good of doing those things. Putting poems on the web because they wanted to put poems on the web. Making photographs and sharing them with other people out there. Writing blog posts because there's an audience and people would read it. And slowly these big corporations, and the people who used to control everything in the 20th century, have gotten on board. They woke up. They said, "Oh my gosh, the web is a big thing. Let's get over there." And they've slowly been taking over, taking over, taking over, and it feels like it's no longer a clubhouse where a bunch of friends get to hang out. [Doug laughs] It's becoming like a new version of a Hollywood movie studio. Back in the 19th century, when you would have music. It would just be you and your friends with sheet music and playing in the living room and enjoying music. And then it became this late-20th-century, this big machine. You've got to make it. You need a record contract. You gotta get a big, expensive studio to record in, then you're going to go on tour and it's going to be a multi-million-dollar operation and you're going to make millions of dollars. If the web, it felt like for a moment we were going to go back to how things used to be, where it was just humanity sharing and being artistic and creative and communicating and now it feels like those corporations went, "Wait a minute, we need to get control over everything again. Or else we're going to lose it."

- Jeremy

- This is exactly what Jonathan Zittrain talked about in his book, "The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It." And he did compare it to previous mediums like that, that began in a very open way, that had a very democratic way of publishing and then over time you end up with the big players. The big players end up having the control, the big players end up dictating what the majority of people can consume. I don't think it's inevitable that the web would end up like that. I'm absolutely fine with the internet being used in that way. When Netflix says, "We want to be able to provide our movies on the web with DRM or we won't provide it on the web." Then that's when I say, I'm absolutely fine with them not providing it on the web. The internet is a big place. They've still got other ways other than the web, other than the web browser, to provide that content with DRM and I'm absolutely fine with them doing that. But within the web browser, where we still at least have some semblance of that idea that anybody can publish, anybody can consume, you know. I think we need to fight to keep that ethos of the web.

- Doug

- I obviously agree. I mean, that's the whole thing that W3C tries to do, is tries to empower people to create things and to distribute them. I don't have that opinion because I work for W3C. I work for W3C because I have that opinion, right? I would say I'm a little more optimistic about things. I think that, one, even if corporations, big faceless corporations, are distributing their content on the web, that doesn't stop other people from also using the web. It doesn't lock it down. There are other things that would get in the way more of user freedom that we don't have time to go into on this. [Laughs] I still think that the web on the whole has ended up with a net increase of people being creative and finding audiences for their creativity than for it being, you know, something that is just another distribution mechanism for big corporations. Since there has been TV, there have been small stations that have had small distributions that people couldn't see. Now, far more people can find your YouTube channel than could ever have encountered your community public television thing. And I think that the web is going to continue to be this place where people can create and share. I don't think that we should get depressed about the notion about, just because corporations are also using this, that means we can't use it. We can.

- Jen

- Yeah, that's true.

- Jeremy

- I think in general that I agree. The web layer has actually still got its ethos and is pretty democratic and pretty open. I think you're right, that the things to be more concerned about are further down the stack. Things like net neutrality, obviously. That's not on the web side of things, that's on the network layer, that's a much, much bigger concern.

- Jen

- I need to jump in here with out last sponsor for the day. Squarespace. Speaking of being creative and making your own space and putting your own work out there. This is one way. There are many ways. This is one way to do it. It's an all-in-one platform that makes it fast and easy to create your own professional quality website, portfolio and online store. For a free trial and 10% off you can go to squarespace.com and insert the code JENSENTME. Squarespace constantly updates their platform with new features, new designs and more support. They have beautiful templates for you to start with. Tons of style options for you to adjust so you can really just create your own space online. Everything is drag-and-drop so it's easy to add content from your desktop and rearrange the elements of that content within the page by just dragging and dropping. Squarespace makes sure that your site automatically looks great on any device because every Squarespace website has its own unique, oh look, see here, they say "mobile design." I'm not going to read that. I'm going to be "responsive design." [Doug laughs] It's responsive. All their themes are responsive. And you can hook up Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Instagram, Google, all that stuff. You don't have to know so much technical, so many technical things about how to do that. You don't have to take time to go figure out the code. You can focus on your own writing, your own photography, your own video, your own physical store if you have one, a shop, whatever it is that you're working on. Just click some buttons and fill out some forms and Squarespace will take care of all this other social, blahty blah stuff for you. They also have an ecommerce platform so you can set up a shop online and sell things. It will be all PCI-compliant and blahty blah, all the stuff that you don't want to know about necessarily. Bam, you have a store. It is incredibly easy to use but if you need some help, there are over 70 Squarespace employees on their customer care team located in New York City and in Dublin. They're available for 24/7 live chat and email support. You can try it free, no credit card required. And if you decide to purchase, plans start at just $8 a month including domain name if you sign up for the year. Get your 10% off and support The Web Ahead by using offer code JENSENTME. Thank you to Squarespace for supporting 5by5 and supporting The Web Ahead.

- Jen

- So, Mozilla. Will you guys chime in a bit about how Mozilla has been an advocate for not having DRM on the web and how people, some people are upset with them because now they've agreed to do EME and they're not continuing to push for... what's up with Mozilla?

- Jeremy

- Well, I guess this is how things normally go. They also said they wouldn't support H264 and then said, "Yeah, ok, we will." And they weren't going to get behind EME and then, "Yeah, ok, we will." Or maybe it's not EME they're going to get behind but the idea of DRM on the web. Again for the reasons given. That, "Oh, it's inevitable, it must happen, therefore we're going to go along with it." Which I don't agree with, as I said, I'm fine with a web without those content providers. Without the DRM. But, yeah. Mozilla had one position and then they changed it. To be fair, very, very, very reluctantly.

- Doug